Black History in Pasadena

By A Noise Within

March 15, 2021

We began preparing an overview of Black history in the city of Pasadena as a part of Black History Month, but as we sought insight from local Black community leaders, we found a beauty in taking the time to hear the deeper stories and remembrances and recollections. Although February may be over, Black history is a year-round learning experience. With this in mind, we want to share what we have with you now.

We go through the lives of prominent civil rights activists, explore histories of local churches, and cover several major events in Pasadena, including the construction of the 210 freeway and the segregation of the public schools and pool. This is by no means a complete account, but we hope that you find inspiration to learn even more.

Pasadena Figures

Jackie Robinson

In 1920, Jackie Robinson’s mother moved the family to Pasadena, California as the first African American family to live on Pepper Street. Robinson attended Muir Tech (later known as John Muir High School) and Pasadena Junior College, where he excelled as an athlete and as a baseball player, as everyone else in the country would soon come to know.

While attending PJC, Robinson broke countless records as an all-star athlete in four sports: track and field, basketball, football, and baseball. In football, he holds a PJC record for longest run from scrimmage, 99 yards, and he held records that were not broken until 2001 for most touchdowns and most points in a season. In track and field, he broke his own older brother Mack Robinson’s national community college record for the longest broad jump at 25 feet, 6-1/2 inches. After attending UCLA and serving in the military, he would eventually join the Brooklyn Dodgers in 1947. Robinson went on to a Hall of Fame career and is the only player in the game’s history to have his number 42 retired by all teams in MLB.

Pasadena City College’s football stadium is named after him and his brother Mack—Robinson Stadium—and the Lancers baseball team plays at off-campus Jackie Robinson Memorial Field, located at Brookside Park next to the Rose Bowl.

Loretta Thompson-Glickman

Before becoming Pasadena’s first Black mayor, Loretta Thompson-Glickman was a teacher at Pasadena High School and a jazz singer in small local clubs. She toured with the New Christy Minstrels before leaving to start a family in 1975. Two years later, she campaigned for office as city director from District 3 in Northwest Pasadena, a predominantly Black area. Thompson-Glickman was backed by Dolores Hickambottom, who had a deep knowledge of and influence in Pasadena, thanks partly to her marriage to native Pasadena resident and attorney Elbie Hickambottom.

In 1977, Thompson-Glickman became the first Black woman elected as a Pasadena city director, then a few days later became the first city director to become a mother while in office. She served as vice mayor for a while before being elected Mayor by her fellow city directors. In 1982, she became the nation’s first Black woman mayor with a population exceeding 100,000. Thompson-Glickman is credited with making local government more accessible to residents of Northwest Pasadena, resulting in residents becoming more involved in civic affairs.

“She was really talented,” said Alma Stokes, a longtime Pasadena resident. “That’s why she made such a good mayor. They thought they could run her, but they couldn’t. She was smart within her own self.”

Octavia Butler

Octavia Estelle Butler, known as the “grand dame of science fiction,” was born in Pasadena on June 22, 1947. She received an Associate of Arts degree in 1968 from Pasadena Community College, and also attended Cal State LA and UCLA. During 1969 and 1970, she studied at the Screenwriter’s Guild Open Door Program and the Clarion Science Fiction Writers’ Workshop, where she took a class with science fiction master Harlan Ellison (who later became her mentor), and which led to Butler selling her first science fiction stories.

Butler read science fiction growing up, but she quickly became disenchanted by the genre’s unimaginative portrayal of ethnicity and class as well as by its lack of noteworthy female protagonists. She began a prolific career doing what she referred to as “writing myself in.” Butler’s stories, therefore, are usually written from the perspective of a marginalized Black woman whose difference from the dominant agents increases her potential for reconfiguring the future of her society.

Ruby McKnight Williams

During the 1930s, Ruby McKnight Williams moved to California from Kansas with the intention of working as a teacher. When she came to Pasadena, however, she discovered that the city did not hire Black teachers. “I didn’t see any difference in Pasadena and Mississippi except they were spelled differently,” said Williams. She would become the longtime president of the NAACP chapter in Pasadena and the first Black board member of the American Red Cross’ Pasadena branch. Devoted to the care of and investment in youth, Williams also served for six years as adviser to the NAACP National Youth Work Committee.

During her NAACP tenure, Williams took up the cause of school and housing desegregation. Twice, she visited the U.S. Supreme Court to witness integration decisions. She also fought and won local redevelopment battles. Meanwhile, in 1946, she married Melvin Williams, and together they worked to beautify their neighborhood and street. In 1966, Westgate Street won a Pasadena Beautiful Award.

Dr. Edna L. Griffin

Dr. Edna L. Griffin was Pasadena’s first Black woman physician. Her father, who died during the 1918 influenza pandemic, was a Methodist Minister who valued education and instilled this in his daughter. Dr. Griffin started her higher level education at Philander Smith College and continued her education at the Meharry Medical School. Dr. Griffin considered pursuing her medical education at USC, but officials told her that the university did not accept Black students into its medical school program. She interned at John Andrew Hospital in Tuskegee, Alabama and practiced briefly in Evansville Indiana before relocating to Pasadena in the late 1930s. In her obituary, Dr. Griffin was credited as being the leader of the efforts to desegregate the Brookside Plunge, now known as the Rose Bowl Aquatics Center.

George Edward Alcorn Jr.

Born in Pasadena in 1940, George Edward Alcorn Jr. is best known for inventing the X-Ray Spectrometer. This invention was widely adopted by NASA and would earn Alcorn the NASA Goddard Space Flight Center Inventor of the Year award in 1984. Alcorn earned his B.A. in Physics in 1962 from Occidental College and his master’s degree in Nuclear Physics in 1963 from Howard University. After Alcorn earned his doctorate in atomic and molecular physics from Howard University in 1967, he spent 12 years in industry as a senior scientist at Philco-Ford, a senior physicist at Parker-Elmer, an advisory engineer at IBM Corporation.

He would later become IBM’s Visiting, and then full, Professor of Electrical Engineering at Howard University. In 1978, he joined NASA and invented his famed invention, the X-Ray Spectrometer.

Community Displacements

In the 1950s, Pasadena residents traveled to Los Angeles and the surrounding area by using the Pacific Electric Railway, also known as the “Red Cars.” Central and Northwest Pasadena thrived with a racially diverse community of working class whites, African Americans, Mexican Americans, and Japanese Americans living in single family and multi-family residencies of all sizes. However, federal officials and the local Chamber of Commerce classified the area as “blighted” in the late 1950s, despite the beautiful houses and the thriving community who lived in them.

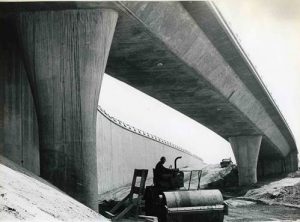

During the 210 freeway’s construction, the white residents of Southeast Pasadena rallied to keep the freeway out of their neighborhoods, leaving the Central and Northwest Pasadena residents with few options when the route plowed through their neighborhoods instead.

Pasadena Star-News editor Lee M. Merriman chaired a “Citizens’ Committee on Freeways” that collaborated with state highway officials on the 210 freeway route. City leaders believed the freeway would solve “transportation problems,” but they insisted the freeway stay away from CalTech, the Pasadena Playhouse, the Tournament of Roses, or “other educational and cultural” sites that made the city “world famous.” Merriman did not mention how the freeway would devastate Pasadena’s citizens of color in the Northwest and Central districts.

Bob Gonzales, whose house lay in the path of the freeway, talked about the neighborhood’s response. “Well, you know what happened at Chavez Ravine? See? The government. The city. Money. We couldn’t do nothing. We couldn’t fight city hall. All those homes that they took down from south of John Muir, that area? Oh, there was some beautiful homes there.”

The 210 freeway’s construction began in the late 1950s and continued through the 1970s. This freeway tore through a vibrant African American business district on North Lincoln Avenue that has never fully recovered. The mixed-income, racially diverse community in Northwest Pasadena was also torn apart. Individuals displaced by the freeway were offered $75,000 for their homes. However, no homes in Pasadena cost less than $85,000, worsening the displacement.

The freeway was just one example of the displacement of the Black community in Pasadena. Throughout the country in the 1950s and 1960s, the federal government provided funding for cities to raze “blighted” or “slum” neighborhoods. Though improved housing opportunities was the ostensible goal, over time, cities used federal funds to stimulate commercial and industrial redevelopment. Through these programs, cities displaced hundreds of thousands of families from their homes and neighborhoods.

Pasadena’s first urban renewal project was known as the Pepper Project. The residents of the area had resisted a project in the most vigorous fashion at their command. In response, Pasadena Redevelopment Agency hired Black professionals, but community leaders continued to resist and said: “Who is going to protect the interests of Negroes? Surely not Pasadena’s white people.”

Despite their efforts, however, all the residents from Washington Blvd to Mountain St and from Sunset Ave to N Raymond Ave were removed from their homes. By the late 1960s, an estimated 299 families had been displaced by urban renewal projects in Pasadena, 91% of which were families of color.

“The area really wasn’t blighted,” said Pasadena resident Alma Stokes. “It wasn’t. It was just Black removal.”

“Desegregation” of Pasadena Schools

In 1970, US district court judge Manuel Real ordered the Pasadena Board of Education to desegregate, making Pasadena the first city outside the South to desegregate its public schools because of a federal court order. Pasadena instituted a busing program to integrate its schools and was released from the court order in 1980. However, the busing program indirectly caused the perpetuation of segregation through other means.

Because private schools were not included in the new plan, people who could afford it sent their children to private schools instead of participating in the busing system. As a result, 30 private schools (53 as of 2019) arose in Pasadena, causing the number of white students taking the bus to dwindle and hardening the grip of de facto segregation in the district.

Desegregation of the Public Pool

Upon opening a municipal pool (called “Brookside Plunge”) in 1914, Pasadena created a “Negro Day” policy to restrict African Americans (and other people of color) to using the pool on Tuesdays. Then in the evening, the city drained the pool and refilled it for white swimmers to use on Wednesday. African American residents formed the Negro Voters and Taxpayers Association to fight the restriction for several decades.

By the 1930s, Ruby McKnight Williams, Dr. Edna Griffin, and other activists joined the protest through the courts and other means. Thurgood Marshall and Charles Hamilton Houston monitored these legal battles with the city of Pasadena. Six African American men tried going to the pool on a different day in 1939 and were barred from entering. The NAACP of Los Angeles then sued and won the case three years later. In response, Pasadena closed the pool until the NAACP got an injunction, forcing its reopening on July 7, 1947, without racial restrictions.

Black Churches

Saint Barnabas Episcopal Church

The African Americans who came to the Los Angeles area did not find a ready welcome in the Episcopal churches, and on June 16, 1909, a meeting was held at the home of Mrs. Georgia Weatherton on South Fair Oaks Avenue “to organize an Episcopal mission,” soon known as St. Barnabas Guild, according to handwritten minutes in the diocesan archives.

St. Barnabas Church itself was founded in 1923 by eight women. Among them were Ellensteen Bevans, Rosebud Mims, and Georgia Weatherton, in whose home on Del Mar Street the first services were held. At times, as many as 29 members were present for worship on Sunday mornings. The congregation was served at that time by a Lay Reader from All Saints Church in Pasadena and the organist from St. Philips Church in Los Angeles.

In the early 1930s, the Dobbins family donated the present property located at 1062 North Fair Oaks Avenue, and Mr. and Mrs. Thomas Fleming made a gift of the current sanctuary, which was dedicated by Bishop Stevens in June 1933.

FAME Pasadena Church

First African Methodist Episcopal Church, the oldest black congregation of denomination in Pasadena, was founded in the fall of 1887, in the home of Silas and Cynthia Carnahan. Under the direction of Rev. I. W. H. Nelson, the formal organization was completed in the spring of 1888. The first pastor appointed to serve the church was Rev. J. R. McClain.

Meetings were held in the Carnahan home until a site for a building was located on North Fair Oaks between Villa and Orange Grove. The church remained there until Rev. William Prince, one of the founders, served as assistant Pastor for over 40 years. In 1910, during the pastorate of Rev. G. W. Tillman, a lot was purchased and a new edifice was built on the corner of Vernon Avenue and Kensington Place.

During the 1960s, the State of California purchased the church facilities for freeway construction. In 1967, under the administration of Rev. Edward P. Williams, Sr., property was purchased on North Raymond Avenue and Penn Street. In 1969, the present church building was completed and dedicated. The new church is a tribute to Rev. Edward P. Williams, Sr.

Friendship Pasadena Church

Friendship Pasadena Church was founded in September 1893 and has been recognized as one of the oldest congregations in the city of Pasadena. Officially named Friendship Baptist Church, it was the first African American Baptist Church in the city.

The Church grew and prospered under the leadership of several ministers until the 1920s, when Reverend W.H. Tillman led the members to acquire a new site and erect the present edifice. In January 1925, Reverend W.D. Carter was called to lead the congregation spiritually and complete an ambitious building project, which stands today as a monument to the heritage of Pasadena’s African-American citizens.

From a ground-breaking ceremony held in March of 1925, Friendship has stood prominently for over 75 years as one of the visible landmark Churches in Pasadena. It is the first African-American related Cultural Landmark designated in Pasadena; recognized as a State of California landmark, and in 1978 was listed on the National Register of Historic Places in the United States of America.

Learn More

We highly encourage you to go deeper with the resources referenced throughout this blog post and listed below to explore the past and ongoing contributions of Black people in Pasadena, Southern California, and beyond. We also encourage you to dive into our blog for our recent Black History Month features with local Black arts leaders to discover their creative journeys and ongoing work.

Special thanks to Alma Stokes for her consultation and insight and to the Pasadena Museum of History for permission to use photos from their archives.

Sources

Barker, Mayerene. “Activist Spends Decades Breaking Race Barrier.” Los Angeles Times, 16 Jan. 1983, digitallibrary.usc.edu/digital/collection/p15799coll118/id/1857/rec/36.

Blumberg, Leonard. “Segregated Housing, Marginal Location, and the Crisis of Confidence.” Phylon (1960-), vol. 25, no. 4, 1964, pp. 321–330. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/274099. Accessed 8 Mar. 2021.

Digital Scholarship Lab, “Renewing Inequality,” American Panorama, ed. Robert K. Nelson and Edward L. Ayers, dsl.richmond.edu/panorama/renewal/#view=-215.01/-734.23/4.24&viz=cartogram&city=pasadenaCA&loc=12/34.1652/-118.1520&project=3864. Accessed 4 Mar. 2021.

Elhachem, Roxanne. “Pasadena Busing Controversy, 9/14/70.” ColoradoBoulevard.Net, 17 Sept. 2019, www.coloradoboulevard.net/pasadena-busing-controversy/.

First AME Church of Pasadena. “FAME Pasadena Church History.” famepasadena.org/about_fame.php. Accessed 8 Mar. 2021.

Foster, Catherine. “Desegregation of Pasadena Schools — 12 Years Later.” The Christian Science Monitor, 28 Jan. 1983, www.csmonitor.com/1983/0128/012850.html#:~:text=Pasadena%2C%20Calif.,Los%20Angeles%20suburb%20to%20desegregate.

Friendship Pasadena Church. “Our History.” friendshippasadena.church/about-us. Accessed 3 Aug. 2021.

Haywood, Dennis. “Black and a Woman, Loretta Thompson-Glickman Was a Trailblazer.” Pasadena Black Pages, 1 Feb. 2019, www.pasadenablackpages.com/black-and-a-woman–loretta-thompson-glickman-was-a-trailblazer.html.

Hudson, Lynn M. West of Jim Crow: The Fight Against California’s Color Line. University of Illinois Press, 2020.

Jones, Rochele. “Octavia Butler: Pasadena’s Grand Dame of Science Fiction.” Pasadena Black Pages, 6 Mar. 2019, www.pasadenablackpages.com/octavia-butler–sci-fi-writer-excelled-in-white-male-dominated-arena.html.

McFadden, Christopher. “31 Highly Influential African American Scientists.” Interesting Engineering, 17 Oct. 2018, interestingengineering.com/31-highly-influential-african-american-scientists.

Pasadena City College. “Jackie Robinson.” pcclancers.com/hof/Jackie_Robinson?view=bio

Pasadena Complete Streets Coalition. “Walking Tour of the African American History of Pasadena.” Izi.TRAVEL, 2020, izi.travel/en/browse/c2e918f7-5a8d-4877-be85-d903cba67255#tour_details_first

Pasadena Museum of History Collection. digitallibrary.usc.edu/digital/collection/p15799coll118/search

Winton, Richard. “Suit Accusing Coach of Racism Stirs Bitter Memories of Pool’s Past.” Los Angeles Times, 1 Mar. 2019, www.latimes.com/archives/la-xpm-2001-apr-16-me-51719-story.html