“Bring out your dead!” Tom Stoppard and the Theatre of the Absurd in Rosencrantz & Guildenstern Are Dead

By A Noise Within

September 21, 2018

By Miranda Johnson-Haddad

Tom Stoppard’s first major hit, Rosencrantz and Guildenstern Are Dead, came well before British comedian and Monty Python member Eric Idle, sounding very bored, exhorted the plague-stricken townspeople to “Bring out your dead!” in Monty Python and the Holy Grail. Yet it is difficult to imagine this film without Stoppard’s play and the literary and theatrical traditions that contributed to it. In many respects, Rosencrantz and Guildenstern Are Dead (aka RosandGuil) enabled not only the Monty Python show and movies, but also the work of many others as well, from the comedy sketches of Stephen Fry and Hugh Laurie, to Stoppard’s own 1998 Oscar-winning screenplay Shakespeare in Love, and continuing all the way to Quentin Tarantino; The Cornetto Trilogy; the zany Pride and Prejudice and Zombies; and even the supremely silly Mystery Science Theater 3000 series.

Playwright Tom Stoppard was born in Czechoslovakia in 1937 and fled the country with his family on the eve of the Nazi occupation, ultimately settling in Britain, where he has been knighted and is now regarded as one of Britain’s greatest cultural heroes. It is notable, however, that Stoppard’s first major success was a play that takes aim at the most iconic and famous work by Britain’s most iconic and famous playwright: Hamlet, by William Shakespeare. Moreover, the entire premise of RosandGuil is essentially a joke based on a single line that is spoken at the very end of Hamlet (Act 5, scene 2, line 411, Folger Library edition), when the Ambassador from England arrives at the Danish court to announce that “Rosencrantz and Guildenstern are dead,” only to find most of the court lying dead in the throne room and no one left alive to thank him for his news. The irony of this moment is amplified by the fact that King Claudius actually never issued any such command, and that Rosencrantz and Guildenstern died because of Hamlet’s craftiness and their own inability to identify, much less adhere to, any kind of moral compass for themselves.

What Stoppard discerns so brilliantly about the line in Hamlet, and what forms the basis for much of the humor in his own play, is the fact that Rosencrantz and Guildenstern do indeed seem to be completely interchangeable characters throughout most of Hamlet. Certainly since Stoppard wrote his play, and probably before, performance traditions around productions of Hamlet have been in on the joke as well. When Claudius, in Act 2, scene 2, says to the two men, “Thanks, Rosencrantz, and gentle Guildenstern,” and Gertrude adds, “Thanks, Guildenstern, and gentle Rosencrantz,” most contemporary productions tend to show either Claudius, or Gertrude, or both, mixing the two men up. In Stoppard’s play, even Rosencrantz and Guildenstern themselves aren’t always sure who’s who, and Stoppard’s genius lies in his ability to convince us that such confusion doesn’t seem like much of a stretch from Shakespeare’s original.

As a play, RosandGuil shows the influence of various theatrical movements that began in the middle of the 20th century, particularly the so-called Theatre of the Absurd as represented in the works of such playwrights as Samuel Beckett, Jean Genet, and Eugene Ionesco, among others. (Beckett’s Waiting for Godot is often cited as a possible inspiration for RosandGuil.) Some literary critics have suggested that the Theatre of the Absurd playwrights drew their ideas and inspiration from Elizabethan drama and literature, making Stoppard’s choice of Hamlet as his jumping-off point all the more appropriate.

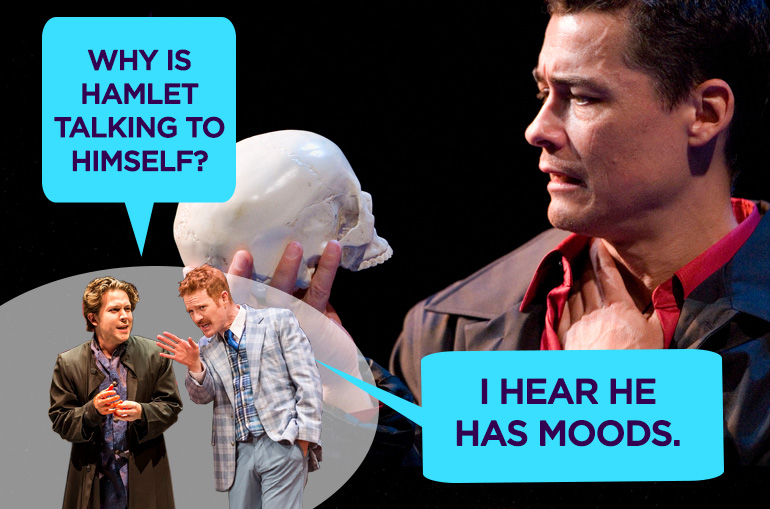

How well does an audience member need to know Shakespeare’s Hamlet in order to appreciate RosandGuil? It certainly helps to have at least a passing familiarity with Hamlet. One running gag, for example, involves Rosencrantz and Guildenstern shaking their heads in confusion over the fact that Hamlet keeps “talking to himself”; but if we are familiar with Shakespeare’s play, we know that Hamlet frequently speaks in soliloquies (including the famous “To be, or not to be” speech), and we can enjoy the joke, one of many that are made at the expense of the clueless Rosencrantz and Guildenstern.

But regardless of how well we know Shakespeare’s Hamlet, we can enjoy Stoppard’s play on its own merits; and even as we shake our heads over Rosencrantz’s slow-wittedness, or Guildenstern’s powerless rages, we also can’t help but feel a pang of sympathy for these two characters, who bumble along, doing the best they can to make their way in a complex world that in the end proves to be just too much for them. Their confused attempts to understand what is going on, and to make sense of their life’s purpose, mirror our own struggles to do the same. In the end, Stoppard seems to say, we can do a lot worse than accept our lot with resignation and laugh at ourselves—but we have the choice as well to do much better than that.

Want to learn more? Read Miranda Johnson-Haddad’s full article and find more resources in our audience guide.

Additional Resources: The 50th anniversary edition of Rosencrantz and Guildenstern are Dead (Grove Press, 2017) includes a new Preface by Tom Stoppard, as well as the cast lists of significant productions from 1966-2017.

The 1990 film version (starring Tim Roth as Guildenstern, Gary Oldman as Rosencrantz, Richard Dreyfuss as the Player, and Iain Glen as Hamlet) was revised and directed by Stoppard himself. (Note: the film’s entry on IMDB includes some fun trivia facts about last-minute cast changes and the filming process.)

On YouTube, see the wonderfully compelling clip of a brief scene from RosandGuil starring Benedict Cumberbatch and Kobna-Holdbrook Smith that was performed as part of a gala celebration at the National Theatre in London on November 2, 2013, entitled “National Theatre: 50 Years on Stage.”

For other “alternate” versions of Hamlet, see the Margaret Atwood short story “Gertrude Talks Back” in her collection Good Bones and Simple Murders (2001); and the Ian McEwan novel Nutshell (2016), which is told from the point of view of Hamlet as a fetus.

For further reading on Shakespeare’s plays, see Marjorie Garber, Shakespeare After All (Anchor Press, 2005), a masterfully insightful discussion of all of Shakespeare’s plays by a well-known Harvard professor. See also Stephen Greenblatt, Will in the World (W.W. Norton & Co., 2004 and the 2016 anniversary edition), in which the renowned Harvard professor discusses several of Shakespeare’s plays, including Hamlet, in terms of how they may have reflected or been influenced by events in the playwright’s own life.

For further reading on the Theatre of the Absurd, see Martin Esslin’s classic work, The Theatre of the Absurd (written in 1961 and reissued in subsequent editions); Esslin himself coined the term “Theatre of the Absurd.”

NOT recommended: the 2009 film Rosencrantz and Guildenstern are Undead. Yes, this is a real thing, and yes, the best thing about it is the title.